Responsibility

by Michelle Moon

Because of Them, We Can is a painting by Columbus, Ohio-based artist Shelbi Toone dedicated to her "ancestors" Kojo Kamau, founder of Art for Community Expression, and other Black artists whose histories are tied to Poindexter Village, a former housing project that will become the state’s first African American history museum where Toone is now project manager. The painting is Toone's homage to people everywhere who inspire and work at arts and cultural institutions.

Because of Them, We Can is a painting by Columbus, Ohio-based artist Shelbi Toone dedicated to the generations of people who inspire and work at arts and cultural institutions.

Reopenings: What Museums Learned Leading through Crisis is a special series of reports by the American Alliance of Museums that aims to capture the broad scope of long-term lessons, mindsets, and leadership practices museums can learn from their handling of the COVID-19 pandemic to ensure they can weather future crises.

In this report, titled Responsibility, the third and final part of our Reopenings series, we look at the pandemic's long-term effects on museums' most important asset: their people.

Through case studies and multimedia that center and amplify the voices of all types of museum professionals at all levels of leadership, we highlight the human-centered management practices that emerged from the pandemic era, offering strategies museums can consider embracing to fulfill their responsibility to take care of their own.

We thank the National Endowment for the Humanities for its support of this project through its Sustaining Humanities through the American Rescue Plan (SHARP) program.

– American Alliance of Museums

Land Acknowledgement

We acknowledge the ancestral lands of the Piscataway people, the lands on which the American Alliance of Museums office is located. We encourage you to use this native lands map so you can learn what lands you occupy—visit: native-land.ca.

Image credit: Bluecadet

Image credit: Bluecadet

As the pandemic struck, like Alice in Wonderland or Dorothy in Oz, museum workers found themselves cast into a completely new reality.

Lengthy closures and stay-at-home orders unmoored us from the buildings and collections that normally anchored our work.

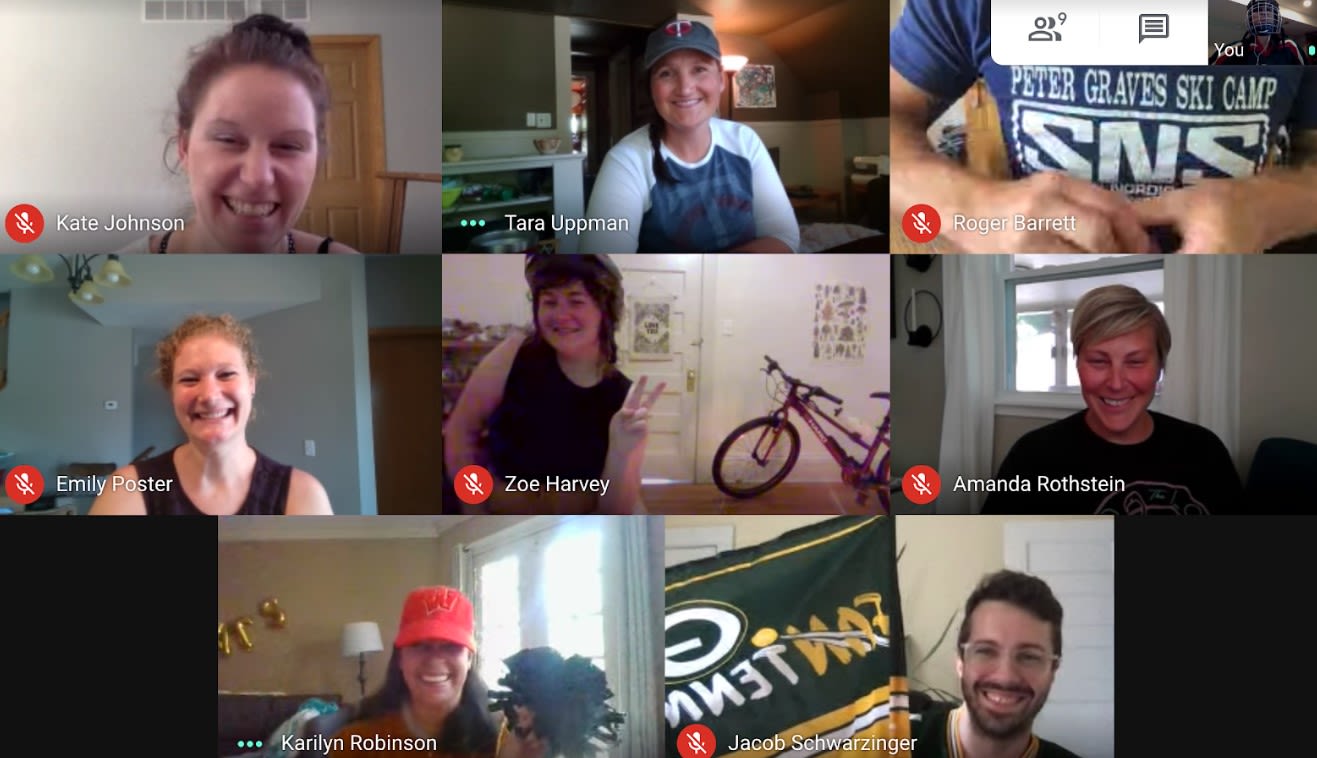

Suddenly, we saw one another in new ways—with the Zoom window as our looking glass. Looking so directly at one another (in some cases for the first time) brought home the powerful realization that museums are made of people.

This strange, unanticipated intimacy generated an intense focus on who we are, not just the work we do. As individual lives blended more visibly with professional capacities, museum workers at all levels developed a keener awareness of how we support and care for one another.

This focused consideration of the people who inhabit museum workplaces, and how they can best relate to one another and to the work at hand, is long overdue.

Interactive Graphic: In Crisis, A Museum Community Finds Its Voice

The early days of the pandemic lockdown saw an intense flurry of activity among museum professionals as they grieved the loss of normalcy, and in some cases the loss of their jobs and with it their identities.

Disoriented and in shock, they needed guideposts and benchmarks, some way of navigating the unknown, and sought out one another for answers.

Andrea Jones of Peak Experience Lab was among the first to dive into the fray with one of the earliest thought pieces that helped museum workers begin to synthesize the chaotic experience into responsive museum practice. Her widely shared blog post “Empathetic Audience Engagement During The Apocalypse” focused not only on museum users, but on museum workers, too, who were going through a tumultuous moment of transition. Seeking to make a visual record of Jones's ideas as well as museum workers' feelings, struggles, and anxieties, Emmie Kell created an original illustration titled What We've Learned in Week One of Social Distancing & Lockdown.

Over the course of the pandemic, both Jones's ideas and Kell's drawing would become a Rosetta stone into museum workers' state of mind as they coped with the crisis.

For AAM's Reopenings project, with Kell's permission, we've created an interactive graphic from her illustration and combined it with recent audio clips of museum professionals (most of whom chose to remain anonymous) sharing their thoughts about the biggest lessons they learned from pandemic work and life. The audio was recorded by AAM via Chicago Scenic Studios' StoryStation booth at AAM's Annual Meeting & MuseumExpo in May 2022.

Taken together, this audio-enhanced, updated reinterpretation of Kell's sketchwork—now titled What We've Learned After Three Years of Pandemic Work and Life—offers a unique then-and-now window into the psyche of museum professionals and how they processed the chaos of the pandemic, as told in their own words.

It illustrates the biggest lessons museum professionals feel they've learned and the time-tested values they discovered they cherished both at the beginning and tail end of the COVID-19 pandemic.

To start the interactive graphic, scroll down and click on any part of the text in the quote boxes to play the audio.

- Anonymous, May 2022

- Anonymous, May 2022

- Anonymous, May 2022

- Rachel Parham, Senior Archivist, NBCUniversal, May 2022

- Anonymous, May 2022

- Mia Buch, Museum Educator, Des Moines Art Center, May 2022

- Terri Freeman, Executive Director, Reginald F. Lewis Museum of Maryland African American History and Culture, May 2022

- Anonymous, May 2022

- Abena Robinson, Education Coordinator, Ah-Tah-Thi-Ki- Seminole Museum, May 2022

- Anonymous, May 2022

- Ana González, Executive Director, Panama Canal Museum, May 2022

- Anonymous, May 2022

- Anonymous, May 2022

Though the professional management literature on museums has long included reference points like salary surveys, model job descriptions, succession plans, and organizational structures, until very recently it has been largely silent on the topic of employee care.

It has offered little guidance on simple questions like:

- How should compensation for museum work relate to the local living wage?

- What should a museum organization do to support the general wellbeing of its employees?

- Are there ways to reduce the strain of solitary leadership roles?

- How can museums position themselves financially and structurally to protect investment in staff talent, even when sudden storms arise?

These questions, foregrounded by the upheavals that began in 2020, are bringing museums to deeply reconsider their approaches to human resources and management. In the process, they are beginning to participate in a profound turning point in the philosophy of organizational management across sectors: the turn toward empathy.

What can we learn from museums that did not just survive the crises that emerged in 2020, but have thrived in them, building positive work cultures that lead to meaningful relationships with their communities? What can they tell us about museums as workplaces?

This report will highlight several case studies of museums whose leadership and management practices—stress-tested during a once-in-a-lifetime pandemic—can help us begin to answer these questions.

LEADING WITH HEART

In fall of 2022, Michelle Moon, author of AAM's Responsibility report, began her search for case study museums and took to Twitter to ask the museum professional community this simple question:

"Can anyone name a #museum that took good care of staff over the past few years?"

Here's what they said:

In her studies of strategic management, Rita McGrath divides the history of organizational management into three eras.

In the first, coming on the heels of the Industrial Revolution, organizations focused on execution—arranging people and resources into a machine-like structure that could produce specific outputs. In the world of museums, this era saw passionate founders creating the earliest formal museum organizations and establishing functional departments within them to produce the outputs we know as collecting, conserving, and exhibiting.

The second era—the era of expertise—defined the management approaches of the mid-to-late twentieth century. As post-World-War-II expansion created more complex organizations, management consulting grew into a booming enterprise, with theorists applying concepts from psychology, sociology, scientific measurement, statistics, and beyond to optimize them as systems.

This style of managerial thinking has had a profound impact on museum management. As museum work moved from vocation to profession over the course of the twentieth century, practitioners delved into the world of corporate enterprise for ideas about how to manage their growing number of activities, services, and constituents.

It became common for cultural management experts to draw parallels like this one by organizational theorist Laurent Lapierre, published in 2001:

“In many respects the management of an arts organization is not unlike that of a commercial enterprise. Both offer products or services, target specific markets, seek to convince potential customers to buy the product or service offered, and set up controls to ensure the judicious use of material and financial resources….[It is only the] nature of the product offered by arts organizations that sets them apart from other types of business.”

In the decades between the pressures leveled by the austerity of the early 1980s and those of the banking crisis of 2008, professionalizing museums absorbed most of the key practices of for-profit management theory: management by strategy and objective-setting, tracking key performance indicators for activities and personnel, long-range planning, ROI measurement, project management, logic models, quantifiable data, and outcomes-based management.

As the twenty-first century unfolds, we may be witnessing the next great change.

McGrath argues that we are moving into a new era of management thinking guided by the principle of empathy.

As customers in the experience economy seek more meaningful connections with the organizations they patronize, those who work in those organizations are asking for more meaning, too. This, McGrath says, “changes the nature of the employment contract.”

Institutions designed for the “business-as-machine era,” she writes, are now often seen by employees as promoting inequality and being so results-driven as to disregard the quality of their experience.

“The challenge to management,” McGrath urges, “is to act with greater empathy...figuring out what management looks like when work is done through networks rather than through lines of command, when ‘work’ itself is tinged with emotions, and when individual managers are responsible for creating communities for those who work with them.”

The crises of the pandemic era have accelerated this shift.

Watch AAM's CEO video interviews featuring:

- Micah Parzen, CEO of The Museum of Us

- Alison Rempel Brown, President and CEO of Science Museum of Minnesota

- Jorge Zamanillo, Founding Director of National Museum of the American Latino

- William Harris, President and CEO of Space Center Houston

...as they share how their leadership practices have changed since navigating the pandemic crisis.

Micah Parzen, CEO of Museum of Us, discusses how his museum's workplace culture has been transformed because of the pandemic. Filmed in May 2022 at the AAM Annual Meeting & MuseumExpo in Boston.

Micah Parzen, CEO of Museum of Us, discusses how his museum's workplace culture has been transformed because of the pandemic. Filmed in May 2022 at the AAM Annual Meeting & MuseumExpo in Boston.

Alison Rempel Brown, President and CEO of Science Museum of Minnesota and AAM board member, shares why DEAI is necessary for a healthy, robust workplace. Filmed in May 2022 at the AAM Annual Meeting & MuseumExpo in Boston.

Alison Rempel Brown, President and CEO of Science Museum of Minnesota and AAM board member, shares why DEAI is necessary for a healthy, robust workplace. Filmed in May 2022 at the AAM Annual Meeting & MuseumExpo in Boston.

Jorge Zamanillo, Founding Director of National Museum of the American Latino, and AAM Vice Chair shares the biggest lessons he's learned from the pandemic. Filmed in May 2022 at the AAM Annual Meeting & MuseumExpo in Boston.

Jorge Zamanillo, Founding Director of National Museum of the American Latino and AAM Vice Chair, shares the biggest lessons he's learned from the pandemic. Filmed in May 2022 at the AAM Annual Meeting & MuseumExpo in Boston.

William Harris, President and CEO of Space Center Houston, discusses the pandemic's long-term legacy on museum leadership practices. Filmed in May 2022 at the AAM Annual Meeting & MuseumExpo in Boston.

William Harris, President and CEO of Space Center Houston, discusses the pandemic's long-term legacy on museum leadership practices. Filmed in May 2022 at the AAM Annual Meeting & MuseumExpo in Boston.

Micah Parzen, CEO of Museum of Us, discusses how his museum's workplace culture has been transformed because of the pandemic. Filmed in May 2022 at the AAM Annual Meeting & MuseumExpo in Boston.

Micah Parzen, CEO of Museum of Us, discusses how his museum's workplace culture has been transformed because of the pandemic. Filmed in May 2022 at the AAM Annual Meeting & MuseumExpo in Boston.

Alison Rempel Brown, President and CEO of Science Museum of Minnesota and AAM board member, shares why DEAI is necessary for a healthy, robust workplace. Filmed in May 2022 at the AAM Annual Meeting & MuseumExpo in Boston.

Alison Rempel Brown, President and CEO of Science Museum of Minnesota and AAM board member, shares why DEAI is necessary for a healthy, robust workplace. Filmed in May 2022 at the AAM Annual Meeting & MuseumExpo in Boston.

Jorge Zamanillo, Founding Director of National Museum of the American Latino, and AAM Vice Chair shares the biggest lessons he's learned from the pandemic. Filmed in May 2022 at the AAM Annual Meeting & MuseumExpo in Boston.

Jorge Zamanillo, Founding Director of National Museum of the American Latino and AAM Vice Chair, shares the biggest lessons he's learned from the pandemic. Filmed in May 2022 at the AAM Annual Meeting & MuseumExpo in Boston.

William Harris, President and CEO of Space Center Houston, discusses the pandemic's long-term legacy on museum leadership practices. Filmed in May 2022 at the AAM Annual Meeting & MuseumExpo in Boston.

William Harris, President and CEO of Space Center Houston, discusses the pandemic's long-term legacy on museum leadership practices. Filmed in May 2022 at the AAM Annual Meeting & MuseumExpo in Boston.

Museum people, among others, are asking for an increased priority on empathy.

The influences of the business-as-machine practices of the twentieth century had a tremendous and largely positive impact on museums; they helped turn around underperforming institutions, raised the bar for professional standards of practice, and reduced the risk of waste and malfeasance.

At the same time, pandemic-era pressures may have revealed that the hard-nosed logic of systems designed to produce profit at any cost has offered a very limited set of solutions for shepherding institutions through a crisis—or even for operating them in uneventful times.

Though museums can make good use of the tools of modern organizational management, perhaps we are due for a recognition that the enterprise we are in is a fundamentally different one from corporations.

Our bottom line is not only in preserving institutional entities, but preserving public-serving capacity—achieving a positive impact in our communities and investing in people whose individual growth will expand and deepen that impact.

Watch AAM's keynote video "Speak the Truth and Point to Hope" from its annual meeting archives featuring:

- Sandra Jackson Dumont, Director and CEO of Lucas Museum of Narrative Art

- Mikka Gee Conway, Chief Diversity, Equity, and Belonging Officer of the National Gallery of Art

- Ben Garcia, Executive Director of The American LGBTQ+ Museum

...as they discuss how the pandemic has changed museum workplace practices forever.

EMPATHY AS EXCELLENCE

Museums have been in experimental mode for some time.

Scholar Jay Rounds has described our current era as a “paradigm shift” in terms of how we conceive of museums and their purpose.

During this liminal moment, people have been experimenting in and with museums, including with their leadership structures, budgetary assumptions, staff relationships, and employment agreements.

Many of these experiments had set roots long before the pandemic era; from today’s vantage, we can witness how they’ve weathered.

The five case study museums below present new ways of thinking about museum work and the people who do it. Spurred by the collective crises, they are borrowing proven and promising practices from human-centered fields like education, social services, and community organizing and justice work.

Mindfully humble, none would claim to have created a pure ideal of employee-centric work culture. Yet all have taken seriously the responsibility to ameliorate some of the pain points in museum workplaces, and have integrated that ongoing commitment deeply into their institutional practices.

They are increasing emphasis on employee care and wellbeing.

They hold themselves accountable to professed values as they develop more equitable practices for hiring, compensation, and advancement.

They use business practices smartly to secure the solid foundation they need to be good employers.

And they work with, not against, their staff to constantly improve the museum as both workplace and public service.

In the five case studies that follow, we’ll look at some of these practices and what we can learn from them, including how to:

- Share Leadership

- Plan for People

- Focus on the “Human” in “Human Resources”

- End Payday Precarity

- Embrace the Activist Workplace

Image captions

Share Leadership

From Henry Ford to Jeff Bezos, CEOs have been given star status in our culture, portrayed as singular visionaries capable of total organizational leadership.

This has extended to museums too, which overwhelmingly depend on a single CEO to define direction and produce results. But pandemic-era crises put these CEOs under a bright, hot spotlight.

Overnight in March 2020, and in the weeks and months to follow, they were asked to pull rabbits out of hats: develop budgetary solutions and scenario plans, make difficult employment decisions, and continue to deliver on their missions—all while surfing the daily changing tide of setbacks and opportunities.

These highly visible CEO decisions were wide open to critique—and it came.

The crises fueled “CEO skepticism,” in which museum workers asked: is loading power, responsibility, and expectation onto a single person really the best way to lead complex organizations like museums that not only have business metrics to meet, but also social value to generate?

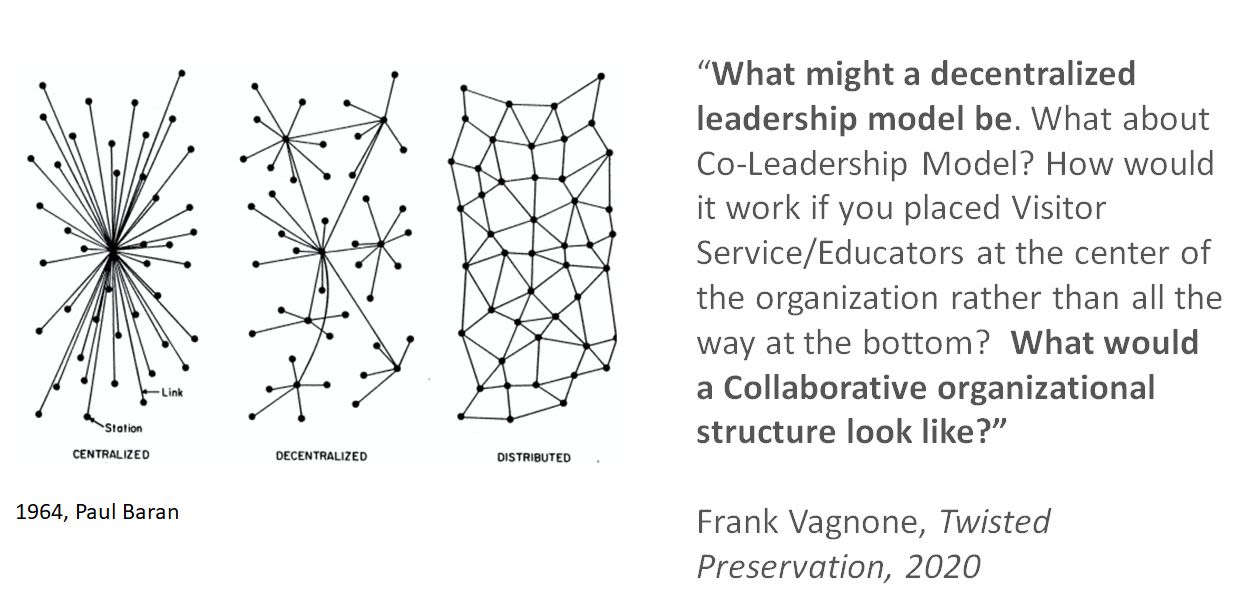

This critique of the classic hierarchical pyramid is not new.

By the 1950s, an increase in “knowledge work” generated alternatives to militaristic, command-and-control traditions and rigid hierarchies. New hub-and-spoke models, matrix structures, or “flat” startup-style organizational charts promised to liberate workers from some of the problems of traditional hierarchy: authoritarianism, distance between managers and work being done, bullying, self-interest, etc.

Despite this experimentation, though, hierarchy has never fully disappeared.

It’s proven a reliable way to steward energies while organizing human effort to get work done in many domains at once—work that no individual could see through from end to end.

The structures of hierarchy also provide “psychological rewards” meaningful to many workers, such as the authority to use special expertise.

In the words of organizational behaviorist Harold J. Leavitt, given the dearth of viable alternatives, “it seems more sensible to accept the reality that hierarchies are here to stay and work hard to reduce their highly noxious byproducts, while making them more habitable for humans and more productive as well.”

But accepting the need for some hierarchy does not have to mean falling back on the classic narrowing pyramid.

One alternative is in experimenting with distributed or shared leadership models. In some ways, these models are not a radical change from normal ways of working, but an acknowledgement of how things already are, which can lead to healthier outcomes.

In the 1940s, Cecil Gibb noted that an organization’s “head,” though imbued with structural power, was not always its true “leader.”

Leaders, in fact, are found throughout an organization; all workers, no matter their position, have influence on the organization’s culture, outputs, and values. Intentionally creating a culture of distributed leadership can help bring “hidden leaders” to the table for productive action.

Shared leadership questions the conception of leadership as an individual phenomenon, envisioning it instead as the property of a group. A leadership team can take on responsibilities formerly united in a single CEO.

This model brings distinct advantages. It can add capacity, removing the one-person bottleneck at the top who needs to review and respond to every activity.

It can increase the diversity of identities, perspectives, and voices that are equally empowered to steer the organization.

It can mitigate the over-influence of a single personality—balancing that person’s flaws and complementing their strengths.

It can ensure that a higher level of expertise is brought to each functional area of senior management by a true specialist in that domain.

And it can vet decisions from many possible angles.

Recognizing these advantages, an increasing number of museums are experimenting with the practices of shared and distributed leadership.

CASE STUDY

The roots of the Peale Center for Baltimore History and Architecture extend back more than two hundred years.

But its current incarnation dates to 2012, when a friends group restored the original Peale Museum as a center for culture, art, and history, with a focus on marginalized and untold stories from the community.

Today, the Peale’s mission is “to create a place where physical and digital exhibition spaces are accessible to everyone, where community members and students can take creative risks, connect with fellow collaborators, and share their stories about Baltimore and beyond.”

Initially, Nancy Proctor was recruited to be the Peale’s first director.

But as the mission developed, Proctor recognized that this new museum would need to “rethink systems and structures that perpetuate inequity and injustice in society and our organization.”

One of those structures was the traditional single-CEO model.

While working with the Baltimore Roundtable on Economic Development to help establish the museum, Proctor and the team began asking themselves what a different leadership path might look like. Together, they developed and proposed a shared leadership model to the board, and secured its support.

Proctor’s title transitioned to Chief Strategy Officer, responsible for strategic planning, partnerships, and developing new revenue opportunities.

Her work is now complemented by three partners in parallel positions: Kim Domanski, who oversees operational areas as Chief Operations Officer; Jeffrey Kent, who focuses on artist relationships and curatorial work as Chief Curator; and Krista Green, who manages the museum’s artist-led collaborative program as Grit Fund Program Manager.

As the pandemic unfolded, the leadership team found this structure a helpful counterbalance in the ambiguous decisions they faced. It helped them broaden their range of ideas and check their thinking against one another.

Agreements were reinforced, and disagreements generated productive analysis of critical questions. “I’ve found it really without exception better than being a sole leader. I infinitely prefer it,” Proctor said. “We are able to be more responsive and imaginative. We make better decisions. My colleagues think of things that would have never occurred to me.”

Domanski echoes the idea that sharing leadership multiplies strengths: “Not only does it expand our knowledge and expertise but also helps us focus in when we have that common ground.”

It's important that teams are composed of complementary talents and styles, Green said. “You can’t be looking for a supplement to follow you.…Trust is really important—a willingness to let go and hear different perspectives and voices.”

One challenge for a newer organization adopting shared leadership is the need for agreed and documented policy.

Disagreements can be minimized by ensuring that decisions are recorded and can be referenced again, Domanski said. At the same time, the group agrees that it’s important for the process to be fluid and allow for ongoing learning.

The leadership team meets regularly, but each member is empowered to make decisions that affect their area of accountability most—a particular benefit during the pandemic, when other organizations were sometimes stuck on securing levels of approval that slowed responsiveness down.

This clear differentiation of responsibilities is what makes this practice possible. “I wouldn’t want to be a co-director sharing half of everything, but who knows which half,” Proctor said with a laugh.

The Peale’s structure ensures that each leader has their own area of oversight, but is recognized as a strategic leader in their own right.

TAKEAWAYS

Be ready to do the hard work

Sharing leadership is possible, but it takes more, not less, rigorous planning.

Green emphasized that “being part of a worker-led-organization isn’t loosey-goosey. It means you need to have thought about all aspects of managing and administering the program and be equally responsible—what process documents do we create to help support people in doing that?”

It also demands presence, emotional resilience, and mutual respect.

Do the research

Far from pie in the sky, these methods work, and their efficacy is supported by a robust body of research. The Peale drew on literature, learning cohorts, and professional development programs to learn about and define their own shared leadership approaches and gain support in making the transition.

Define decision-making practices

Collaborating on leadership doesn’t necessarily mean that every staff member always gets a vote on every decision.

In shared and distributed leadership, there are still individuals who hold responsibility and have final authority.

But it does mean establishing authentic methods of hearing and incorporating wider voices in major decisions, such as establishing feedback channels available to all staff, and cultivating the group skills to collaborate at a high level of trust and safety.

Embrace collaboration

Recognizing leadership throughout the organization, and sharing power, are likely to become more standard in the future.

As Green put it, “The reality of how we work and who is doing the work is shifting. If we are going to continue to attract and retain talent, we need to look at different structures. Everyone wants to see that their voice is heard. We need to stop thinking in triangles.”

Plan to Care for People

Museum business models were already strained before 2020, then the pandemic tested them to their limit.

Entire revenue streams vanished overnight: admission fees, in-person program fees, gift shop sales, rental contracts, and more.

New projects were much less remunerative; virtual programming could not be monetized to the same degree, and museums felt an obligation to provide more free programs in a time of need. Budgets constructed on pre-pandemic assumptions couldn’t be balanced.

Faced with these unprecedented challenges to their revenue streams, many museums sought to relieve the pressure of the biggest line in their budgets: staff.

So began a wave of layoffs, furloughs, and intentional downsizing. For some, this move may have been driven by forecasting a drop in demand for museum services; in other cases it was driven by a simple fiscal reality: there was insufficient cash flow to keep up with payroll.

How do you avoid ending up in such an immediate payroll crisis? In a word, planning.

As the pandemic underscored, museums that depend heavily on earned and gate revenue need to think ahead about how they would deal with a lengthy closure—whether from another pandemic, natural disaster, terrorist event, or any of the other disruptions that have become part of our reality.

Museums must plan to survive and thrive in many different scenarios, not just drag themselves through crisis on paper. This is not just for ethical reasons, but also financial ones.

When a disruption ends, reconstituting museum operations is far easier if organizations can retain and gain value from skilled and experienced staff, rather than hiring new ones. Calculating the cost of lost productivity and institutional knowledge from workforce turnover may reveal that an investment in financial planning for staff sustainability is well worth it.

The following case study museum demonstrates this. When the pandemic arrived, it figured out how to redeploy its teams to produce outcomes that are far superior to shuttered doors and silence.

And they were able to do so because they were not taken by surprise. They had developed worst-case-scenario plans well in advance, including a cash reserve to see them through.

Image captions

Image 1

Image 1Andy Warhol, Dollar Sign, 1981, © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

Andy Warhol, Dollar Sign, 1981, © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

Andy Warhol, Dollar Sign, 1981, © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

CASE STUDY

The World War I Museum and Memorial (WWIMM) in Kansas City, Missouri, drew wide acclaim for retaining and redeploying staff during the pandemic.

The leadership reassigned all staff members to five project areas: Building and Essential Infrastructure (caring for grounds, buildings, security, and technology); Digitization and Transcription (scanning and transcribing historic journals and letters); Digital Learning (developing digital video, curriculum, webinars, social media, and teacher support); Stakeholder Engagement (maintaining and building relationships with donors and volunteers); and Support Services (tracking and managing finance, HR, board, and ongoing retail fulfillment).

Many staff members crossed functions, finding themselves working with new teammates and learning new skills.

Tracy Dennis, Digitization Specialist, and her daughter work from home on transcription.

Tracy Dennis, Digitization Specialist, and her daughter work from home on transcription.

Among those were the group of sixteen staffers, many from the visitor services department, who joined archivists and digital specialists to transcribe and share hundreds of handwritten letters, diaries, and journals left by World War I soldiers. As one of the rare bright spots of pandemic news, this project made headlines and captivated virtual audiences with a new glimpse of the past.

How was this fast pivot possible?

Because the groundwork had been laid long before.

Years earlier, President and CEO Matthew Naylor began working with his board to address the lack of working funds that tends to be endemic in nonprofits.

They modeled alternate financial plans to respond to hypothetical scenarios of revenue loss, identified fallback cuts that could be made to adjust for budget shortfalls, and asked managers to think ahead about where they could economize if they had to.

In the end, they decided to plan for a cash reserve sufficient to cover 180 days of disrupted operation.

Years of modest surpluses, and a portion of the museum’s fundraising, were rolled into a rainy-day fund to support this goal. When the pandemic began, that fund could cover 155 days.

“Sometimes nonprofits present the idea that we shouldn’t be making money,” Naylor said. “But it is a problematic business model to educate our donors as though we shouldn’t be using our resources for the wellbeing of the mission.”

And the wellbeing of the mission, Naylor said, depends on being able to support the staff who carry it out through thick and thin.

“When you’re hiring someone, they are entrusting you with a lot—their family, their housing payments, other needs. I, the team, the board, we share that responsibility. So one of the factors we have to pay attention to is to have sufficient working capital, so we can confidently commit to the mission,” he said.

Thanks to this preparatory work, the team was ready in February 2020 when they began looking with concern at the progression of COVID-19. They started to identify projects, like transcription, that had been on hold until the ideal time to work on them. These projects were not busy work, but tasks that moved previously identified priorities forward.

A WWIMM employee's work-from-home setup for transcription.

A WWIMM employee's work-from-home setup for transcription.

“Our goal was to balance our commitment to staff with the financial health of the organization,” Naylor said. “As we were closed, we sought to focus on important mission-focused activities that support the long-term success of the institution, and respond to the needs of our audiences.”

Ultimately, 40 percent of the staff were assigned to tasks they would not normally have worked on before.

Naylor called it “a hugely productive time for the organization,” with ten thousand pages of scanned letters and diaries undergoing transcription, a surge in online engagement, and new team combinations bringing liveliness to the organization. Much of the resulting work is now being used in a large-scale gallery refresh featuring new exhibitions.

In hindsight, the value of building the cash reserve is obvious.

But before the pandemic, it sometimes led to complicated conversations, such as how you balance investing in an organization’s practical needs in the present and retaining earnings to build working capital and reserve for the future.

In good times, it can be hard to justify reserving funds that could otherwise go to salaries, equipment, or new positions. To ensure that one priority didn’t cannibalize the other, WWIMM coupled its reserve planning with a compensation plan that included annual salary increases and plans for new hires.

In many ways, the museum’s pre-pandemic planning bucked conventional museum wisdom.

Nonprofits are often discouraged from running a surplus or banking a cash reserve in favor of running a break-even budget annually.

But WWIMM’s pandemic experience reveals the limits of this approach. The cash reserve bought the museum time and allowed it to retain a full staff, positioning it to get onto its feet more rapidly than others after the crisis, with no lost institutional knowledge.

This didn’t mean the pandemic was painless for the museum—its pandemic revenue losses totaled nearly two million dollars, and outsourced workers like custodial and food service contractors were not eligible to participate in the reassignment project. But it did create stability that left the museum in a stronger position for recovery, and provided security for a great portion of its staff.

TAKEAWAYS

Imagine the worst

This plan came together with relative speed because the leadership had considered large-scale disasters in scenario planning. WWIMM did not have to start from scratch when developing its survival plan; it had already envisioned and rehearsed the major elements ahead of time.

Create an emergency fund

Building and maintaining a cash reserve can seem like a luxury, but for this museum, it was a lifeline. Start with a reasonable goal and measure progress toward it.

Communicate the value of staff

For many years, Naylor had worked to build the board’s understanding of the value of the investment in staff. Starting over after layoffs isn’t always cost-efficient, especially for a small and specialized team. The payoff of a faster recovery may be worth the short-term investment in maintaining a team during a downturn.

Consider visibility

At least one of the five project areas was media-friendly.

Digitization of soldier’s private diaries and journals created positive press for the museum and generated new discoveries.

Finding a way to be present to a public that was unable to visit helped the museum stay top of mind and enhanced its profile at a time when most of the news was bad.

Images courtesy of The World War I Museum and Memorial

Image captions

Focus on the "Human" in Human Resources

The pandemic made it clear: people make the museum.

With collections and galleries closed, museums literally became their people, activating content for the public and moving projects forward without access to buildings and objects.

There’s no question that people are an organization’s most valuable resource—and, like any resource, require care and thoughtful management.

Museums give detailed and thoughtful attention to capital projects and collections projects.

Shouldn’t they invest just as intentionally in human capital?

During 2020 and its long aftermath, workers have needed more care than ever.

After the chaos of closures, museum workers in hyperdrive expanded digital programs and public services.

“We did so much great work,” a colleague confided to me, “and it nearly killed us all.”

This work demanded more, not less time, even as conditions at home (like juggling online school, remote work, and caregiving) competed for limited attention.

Crises of racial justice brought impassioned and sometimes painful discussions into the workplace; staff members worked through institutional responses while dealing with deeply personal impacts, with some bearing more of the burden than others.

It all led to a secondary epidemic of burnout, according to an AAM study.

Times of transition require particular care. While operating from an emergency mindset, as we were in the pandemic, it can be all too easy to triage away the human needs of the workforce. Some museums, though, recognized the need for additional effort.

CASE STUDY

For the Science Museum of Minnesota (SMM), institutional values guided the development of support systems that prioritized wellbeing and staff cohesion, even in the most difficult days.

Several years before the pandemic, the museum conducted a staff-wide initiative to identify core values, define them clearly, and describe how those values show up in the day-to-day work experience at the museum.

Having those values firmly embedded in the work culture gave the team vital anchor points during the early, chaotic days of the pandemic, said Juliette Francis, Director of Human Resources.

“We had to center ourselves on the pieces that really mattered to us, how our values of collaboration, equity, and learning show up in a time we were all doing a great deal of learning, and had no ready answers,” she said.

Thanks to the SMM’s longtime practice of frequent internal surveys, the leadership team knew that communication was of vital importance to their staff. This knowledge allowed the team to prioritize staying in touch, even when they weren’t sure what they would be able to say.

“It was really scary as leadership to know that the staff is looking to you as the North Star, looking for answers that we just didn’t have.…We had to get comfortable with being vulnerable and asking, ‘What’s important to you right now?’ ”

Though it was clear that closures would lead to layoffs—initially temporary, followed by a permanent downsizing in summer 2020—SMM kept certain goals front and center in the process.

One priority was maintaining healthcare benefits for furloughed staff, especially important given the health risks of COVID-19. Leadership also helped staff navigate the complex and non-standard process of unemployment and emergency supplement applications, offering instruction, support, documentation, and the latest information available.

To keep lines of communication open and maintain relationships, SMM also kept email accounts up and running for staff during furlough, and in many cases, let them hold on to the equipment needed to stay in touch. “The tech resources went home with them,” Francis said.

Another decision was to institute a regular newsletter for the staff community, issued weekly during the first twelve weeks of shutdown.

With a 350-person staff, it was vital to keep the flow of information moving throughout the organization. The newsletter contained the latest news about the museum’s responses and plans, vital information about unemployment assistance and healthcare, and tips and resources to support personal wellbeing—ways to connect, have fun, and get outside to lift spirits “in a time that seemed gray,” Francis said.

After laying off about 40 percent of the staff, the remaining workers were left to navigate a new and unfamiliar working reality.

“It was as confusing and lonely for staff that were retained; there was remorse,” Francis recognized. “We needed to understand, how were people really doing? What does our staff need? What do our managers need to support our staff?”

So, SMM began issuing a new bimonthly pulse survey that asked only five key questions to get to the heart of work culture:

- Are you feeling supported by your manager?

- Does leadership have a clear vision?

- Can you see how your role connects to that?

- How do you feel valued?

- How is equity showing up in your role and being centered in the institution?

Data from these pulse surveys informed new strategies to bring people together to solve problems. The museum created new affinity groups, representing cross-sections of staff that focused on cultural needs and projects: an equity group, a values and connections group, and a “one museum, one culture” group. These groups developed action plans to improve the work experience.

In the process, SMM’s pandemic-driven commitment to centering wellbeing and mental health became a permanent institutional priority. Staff at all levels began to reflect deeply on the value proposition of working for SMM.

“A lot of it was personal and very emotional,” Francis said. “We found ourselves all of a sudden dealing with emotions that used to sit outside of the business world and our 8-to-5 schedules. We realized more than ever that the blend and balance between personal and professional was essential part of our functioning together. Learning that early on meant we placed a high priority on maintaining good relationships.”

As time has gone on, the focus has shifted to how staff needs have changed from new ways of working together and the long-term impacts of the pandemic. Flexibility has increased, as the location of work shifted from home to the museum and back again.

Responsiveness is another principle that has stuck. Team leaders ramped up the frequency of one-to-one check-in meetings to make up for the loss of casual catch-ups around the museum building.

Those additional check-ins also needed to be balanced more intentionally with time away from screens. At times staff expressed “extreme virtual meeting fatigue,” said Francis, acknowledging the sometimes more intense cognitive and sensory demand of screen-based work.

SMM’s emphasis on communication, data-driven response, and being open to feedback means that priorities emerge and shift rapidly. But, Francis says, the leadership is learning to accept that.

“What we’ve learned about staff care is that change is continuous.…We make tweaks and augmentations frequently, informed by our staff, our guests, our volunteers, our visitor exit surveys. We have to work to maintain relevance, and to support our staff through these rapid changes,” she said.

As SMM gradually rebuilds its staffing levels, there’s a new emphasis on building out its HR resources to match.

“We learned so much about supporting our staff and we know that to meet the goals we’ve set for our 2030 strategic plan, we need to do this in a different way, and we need more hands on deck to do this work. The staff are our greatest resource. They’re the secret sauce in bringing the mission to life,” Francis said.

TAKEAWAYS

Practice 360-degree listening

To work effectively together, team members need to know how the others are feeling and functioning.

Finding multiple ways to connect, listen, and share about work experience can help identify issues before they become difficult to manage and reveal gaps in support that can be addressed. Regular staff surveys, check-ins, town halls, open forums, and internal newsletters can build attunement.

Know and reference your shared values

Museums with clearly defined, authentic values have a powerful tool at the ready.

Running possible decisions through the values filter can help make a course of action clearer.

Asking whether a proposed idea is in keeping with the values can help rule options in or out. If they’re widely understood, and not just spoken but lived, values can reinforce trust and a sense of community.

Provide emotional and psychological support

In times of extreme duress, expecting staff to compartmentalize grief, fear, loss, and oppression and just focus on work is unrealistic.

Allowing emotion into the room and creating space for vulnerability and honest communication helps people feel less alone.

And calling on professional help—in the form of Employee Assistance Program support, workplace psychologists, or social workers—can offer people resources that build their resilience.

Communicate constantly

Staff members feel greater comfort when they’re hearing from leadership than when they’re not—even if the message is that answers are still being worked out.

It can feel scary to be transparent about what is and isn’t yet settled, but sharing the process, decision-making factors, and possibilities being explored helps people to feel considered and included in the organizational community.

Images courtesy of Science Museum of Minnesota

End Payday Precarity

For many years, conventional thinking about museum careers went like this: Museum jobs may pay less than similar positions in the private sector, but they make up in prestige and satisfaction what’s lacking in the paycheck.

Those on a museum career track should expect to “pay their dues” in low-paying, part-time, or even unpaid positions for years, and then move up the ladder into management where the pay is a little bit better (if still well below its private sector equivalent).

In the end, any sacrifices will be repaid with the privilege of doing such important work.

If these assumptions were ever viable, they no longer are, for many reasons. One is that “just getting by” isn’t what it used to be.

The increasing costs of housing, food, transportation, child and elder care, and healthcare mean that today’s workers get much less for their dollar.

A second is the credentials crunch: Museum workers who have paid for the higher education expected in our field often carry significant student debt that will draw down their budgets for decades to come.

Finally, and most importantly, it’s fundamentally inequitable. In the past, museum work could be the indulgence of a privileged and homogenous few, whose pay was often supplemented by a spouse’s better salary or family wealth.

But with the field becoming more democratized over time, more people are entering it from backgrounds that make accepting submarket wages an impossibility.

Therefore, museums can never achieve goals for full representative diversity without ensuring that wages provide meaningful support to every worker.

Questions of pay equity (and who in the field should be paid at all) have a very long history.

As far back as 1983, an article in AASLH History News asserted:

“Traditionally museum management has relied on an employee’s personal commitment to shared goals to bridge the gap between an actual salary and a fair wage. Those who worked in museums received compensations other than money. They worked for the prestige the work brought them, or in order to associate with the wealthy and cultured, or to have the opportunity to make significant contributions.”

In the time since then, museum compensation was further limited by efficiency and austerity moves implemented in tight times.

Museums employed more part-time and fewer full-time staff, more staff whose work weeks came in at just under the level that would qualify them for benefits, more “casual” or freelance staff whose hours could be cut, and more volunteers filling formerly paid roles.

Not only has the prognosis for museum jobs failed to improve; they’re less stable and remunerative than they were four decades ago.

Just before the pandemic, awareness of systemic inequities in museum employment reached a new level of concern. The viral 2019 Arts + All Museums Salary Transparency spreadsheet created a watershed moment.

Despite the messiness of its data, it represented something new: an openness to sharing information that made it clear how variable, arbitrary, and low museum salaries were. People began to do the math, predicting lifetime earnings and realizing that museum salaries often fall short of the living wage needed to survive in a given location. There was a growing sense that the museum sector was unwilling or unable to properly compensate workers.

Museum budgets have long been built around the assumption of lower-than-private-market wages. Explicitly or implicitly, museums have accepted the notion of the “prestige bonus,” that they are so inherently rewarding to work in they don’t need to compete with private employers on compensation.

But as the Brooklyn Museum’s unionizing museum workers argued (borrowing a slogan from the organizing era of Harvard’s Clerical Union), “You can’t eat prestige.”

Some museums and initiatives have taken strong steps to challenge the norms of underpayment.

Responding to advocacy by the National Emerging Museum Professionals Network, among other influences, many museums have ended unpaid internships.

The Art Institute of Chicago, the Frick Pittsburgh, and others have replaced unpaid docent programs with paid staff educator positions. The Bullock Texas History Museum is developing full-time hybrid positions combining visitor services work with apprenticeships in other departments.

And a few, like the historic house and garden Filoli, are restructuring budgets and planning to generate a living wage.

Image captions

CASE STUDY

When Kara Newport arrived at Filoli as CEO, the board was positioning itself for change.

Aiming to increase diversity and raise the institution’s profile, Newport and the board developed a Diversity, Equity, Accessibility, Inclusion (DEAI) plan that soon led them to look critically at their staffing assumptions.

In California’s San Mateo County, where the cost of living is the fourth highest in the nation, Newport said: “I couldn’t in good faith go to the community and say, ‘Come work for us and I’ll guarantee we’ll underpay you.’ I couldn’t bear the impact of that.”

Filoli began a comprehensive review of compensation and established a Living Wage Initiative, tying the lowest salary in the organization to the minimum living wage for the county (in 2022, defined at $30.81 an hour). It established an incrementally increasing range of salaries from there, with the goal to reach the seventy-fifth percentile of annual wages for the region.

The museum also regularized titles across departments and established a salary range for each position, with a defined low, mid, and high level within that range, transparently linked to demonstrable skills and qualifications achievable within that position.

Compensation agreements also include an enhanced 401(k), increased vacation time, and sabbaticals at seven, fifteen, and twenty years.

Raising all salaries to that level required an initial investment of 750 thousand dollars, with additional growth each year as costs rise.

To make this increase work, the museum restructured its earned revenue programming and created new positions with revenue potential.

Though her board was strongly in support of the changes, Newport emphasizes that in advocating for the plan, she also needed to make clear she understood the risks of being unable to balance the budget if the plan didn’t work, and would assume the consequences of failure rather than expecting them to close the gap. In the beginning, it meant running lean.

“I worked with fewer staff for a long time with dramatic radical growth, but they were paid better,” she said. “It mattered that I had higher quality staff who were committed to the organization. The board saw we could parlay this investment into growth.”

Filoli today unapologetically embraces a “staff-centric” culture.

Newport understands that rubs against the grain of much museum rhetoric, in which the mission is at the center, but she believes this is for the best.

“The staff exists for the mission. If we’re not taking care of the staff, we’re not achieving the mission. We’re failing at that one thing you’ve committed to by not compensating your staff adequately,” Newport said.

According to Newport, Filoli’s metrics are showing the value of the investment.

“Our workforce is now more diverse, more inclusive, more professionalized,“ she says. “People feel valued for their work; turnover is down to 12 percent—normal attrition. I don’t have people commenting any more that they don’t feel valued. We’ve elevated the ability and skill set we compete for in the hiring market.”

In addition to reimagining its compensation, Filoli also retired a longstanding volunteer program.

Surveys showed that the system was a stressor for the staff and an inefficient way to produce the needed outcomes.

Rather than maintaining a volunteer corps to do routine garden work, for instance, Filoli contracted with a local landscaping firm to take it over—a move that brought new partners into the museum community and supported local jobs.

In the place of its old volunteer program, the museum developed a more accessible “service learning” program, inviting individuals, families, or organized groups to join the museum for a few hours of volunteer service work, along with an informative talk or demonstration. As a result, the number and diversity of volunteers has multiplied.

As museums like Filoli pledge to dismantle systemic inequities of race, wealth, and privilege, salaries must be part of the conversation.

“Low wages are a vestige of white supremacy in museums. They are a systemic issue that has to change,” says Newport. “We’re only at the beginning. We’re going to need a lot of experimenting.”

TAKEAWAYS

Reframe thinking about museum salaries

There is no reason museum salaries must be low in comparison to similar work in other sectors. Though it may be a long project to raise wages, it is a worthy goal for a museum not to transfer its economic burdens to its staff.

Recognize wage improvement as DEAI work

Human resources practices are directly connected to goals for equity, diversity, job satisfaction, and employee care.

Conduct a pay equity audit

Salary reviews can reveal legacies of inequity and variability. Knowing where your institution is starting out gives you the information needed to develop corrective plans that eliminate gender and racial pay gaps.

Rethink voluntarism

In recognition of increasing standards of practice and more equitable access to museum resources, consider whether a volunteer program is replicating systems of privilege and access or monopolizing a disproportionate share of resources.

Benchmark your local living wage

How does your museum measure up against it? Benchmarking statistics for regional salaries vs. cost of living may lead to a new understanding of how competitive an institution is.

Embrace the Activist Workplace

CASE STUDY

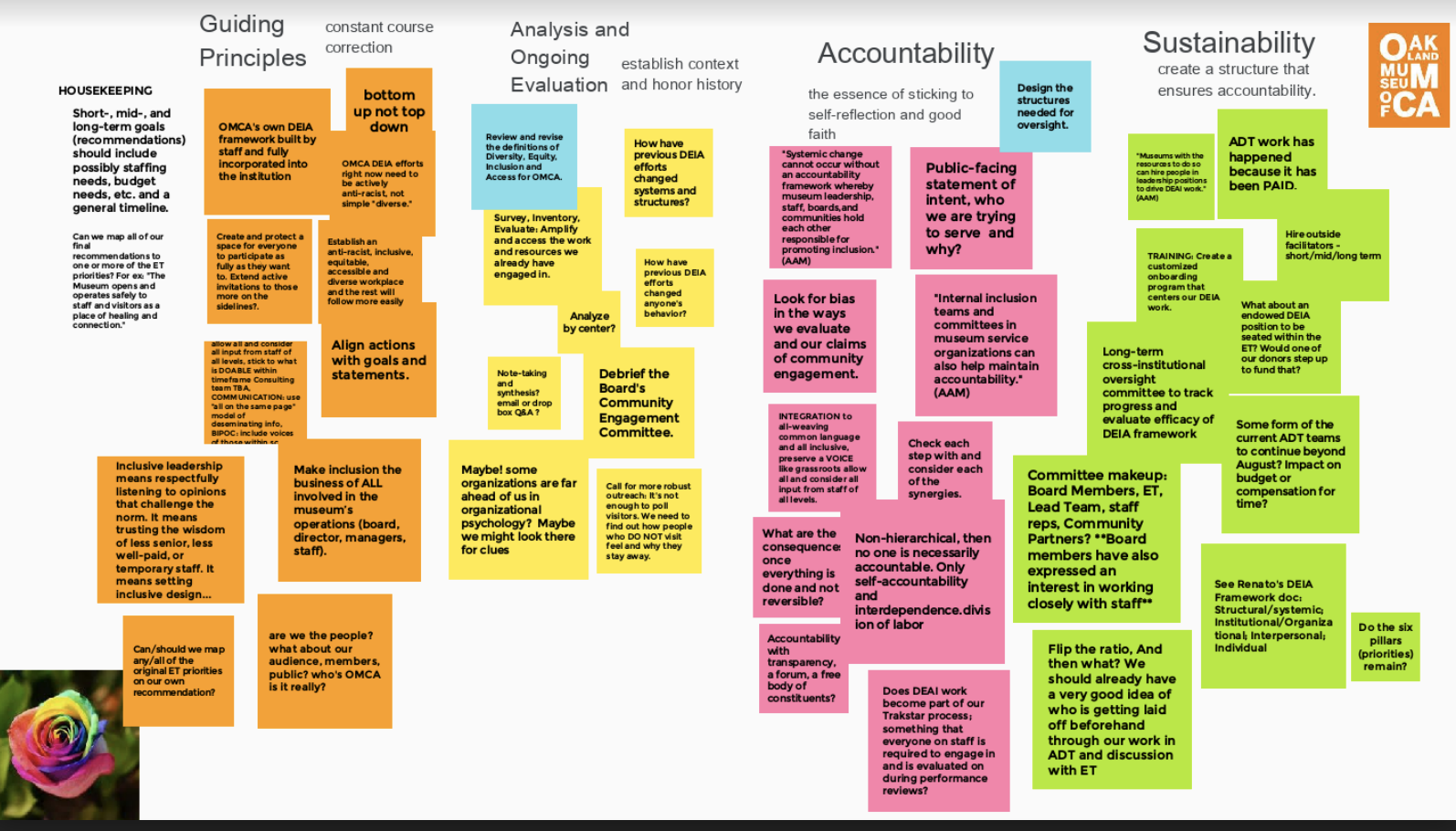

Reeling from the impact of the pandemic, the murder of George Floyd, and the national uprisings against racial violence, the Oakland Museum of California (OMCA) was about to embark on a budgeting process when staff gathered for a town hall meeting.

Drops in revenue would necessitate layoffs and a reworking of museum priorities. But the staff had other concerns foremost in mind: working through the museum’s internal equity issues, particularly as they related to their own employment.

“Especially because we have been an institution held up as an example of this work, we recognized we had to shift our process,” said OMCA Director Lori Fogarty. “We cannot be an organization that cares about equity and then have six people in a closed room sitting and making decisions about the rest of the staff.”

Instead, OMCA’s executive team invited any staff member who wanted to participate in adapting the museum to the demands of the moment to take part in an organizational redesign process.

Fifty people opted in, and from within that group a cohort of young leaders with well-developed community organizing skills emerged—a surprise to many staff. This group shaped the process around anti-racism work, presenting recommendations regarding the museum’s functional areas: fundraising, decision-making, programming, and human resources among them.

The leadership and board had already been working on their own DEAI processes, and committed to listening and responding with care.

“We heard it,” said Fogarty. “We had to do a lot of work behind the scenes to be able to hear these recommendations without defensiveness and resistance, with openness.”

Though recognizing that some workers might have found the initial official response “performative,” Fogarty says that this process “had a profound effect on the way we've gone forward. The shift, for us, was moving away from this idea of ‘us’ and ‘them.’ ”

Rethinking ingrained beliefs about museum hierarchy was a challenge, but OMCA leaders stepped up with vulnerability and presence.

“There was real learning for us as leaders and board members, realizing that there was brilliance, and deep experience, and real knowledge at every level within the institution,” Fogarty said. “Since then, shifts we’ve made are about how we create a ‘healthy hierarchy.’ How do we give voice throughout the organization into major strategic decisions? How do we take into account those most impacted in the decisions?”

Doing deep, personal work on white supremacy and patriarchy has helped the museum’s leadership work in concert with this spirit of direct activism in the museum. Engaging in intentional work with professional facilitators prepared the museum’s executive team to listen, learn, and act with less defensiveness.

“One of our consultants told us to ‘be hard on the structure, soft on the people,’ ” Fogarty said. “These museum conditions are structures. When I could move away and understand that these weren’t critiques of me personally, but critiques around power, forces, money, history—I could think more clearly about how we shift those structures.”

Working in this more participatory way supports the concept “nothing about us without us.”

Staff members now participate on planning teams that deal with routine operational tasks like reconfigurations of office space, budget processes, and investment policy, giving them a hand in the decisions that shape their work.

OMCA has also fostered much more interaction between staff and board as a result of its anti-racism work, helping to demystify the board and giving people at all levels the agency to engage with it.

This relationship-building is essential to overcoming the “us vs. them” dynamic. Shared processes help increase the sense of others’ humanity and build trust.

Defining what “healthy hierarchy” looks like remains a work in process.

“Decision-making is one thing we’re still really grappling with. How do we recognize that we really do have job responsibilities and sometimes need to make decisions that not everyone will agree with, while taking into account those who will be most impacted?” Forgarty explained.

“Where I have seen real progress is where there is transparency around this: Here’s the decision we made, who we consulted, what we considered, the information we were given, and here is how we weighed it. People are willing to give a lot of grace if there is a sincere and authentic desire to be transparent.”

Activism in the workplace isn’t specific to museums, and not likely to evaporate even if crises moderate for a time.

Museum change, like social change, is an ongoing process with no end point. “What I worry about now is the impulse to get back to normal, get back indoors, mount our big exhibitions and go on as if none of this had happened,” Fogarty said. “This work is not done. It’s barely begun.”

TAKEAWAYS

Learn from workers

OMCA’s senior team discovered that the level of staff expertise on social change, organizing, and community facilitation was much higher than they had previously thought.

Throughout the process of developing the museum’s anti-racism initiatives, it was the staff who introduced vital concepts and expanded the range of possibility.

Museums that can act as learning organizations, integrating influences from across the organization, will be more creative, nimble, and responsive to change.

Be transparent

Sharing the context, constraints, and processes used in making decisions can make them more understandable to others, if not fully welcome. Being transparent may also yield new ideas from staff about how to work with a stubborn challenge.

Practice what you preach

Precisely because OMCA is a community-founded institution with a clear commitment to diversity and equity, it is held to account for its own high standards. This alignment between stated values and practice is crucial, as many museums discovered in the aftermath of 2020’s police violence.

Bring the work home

The DEAI work museums do is not just for audiences. It is to help create a mutually respectful, inclusive workplace where people feel a sense of belonging.

OMCA’s team has been working on understanding oppressive systems through participating in the American Alliance of Museums' Facing Change initiative, working internally with coaches and consultants to facilitate vital dialogues on race, gender, power, and identity. Investing in this work has allowed them to be more prepared to respond to the challenges and changes staff are advocating for.

Images courtesy of Oakland Museum of California

Image captions

FINAL THOUGHTS

A museum is more than a machine.

As spaces whose mission-driven work calls on the best of our humanity—curiosity, generosity, respect, learning, sharing—museums will be most successful when the humans who work within them are supported.

Employee care and wellbeing, a living wage, shared leadership, and stable financial structures create the foundation that allows museum staff members to be at their best, bringing the needed creativity, focus, patience, and commitment to their work.

In the age of empathy, museums must make staff experience a priority, from senior levels through to those working in museums for the first time.

Michelle Moon is a consultant recognized for her work on museum interpretation, audience development and program design. Moon holds a master’s degree from Harvard University’s Museum Studies program and a bachelor’s degree in Education and American Studies from Connecticut College. She has served as Chief Program Officer at the Tenement Museum, Director of Interpretation and Evaluation at Newark Museum at Art, and as Assistant Director for Programs at the Peabody Essex Museum.

The National Endowment for the Humanities: Democracy demands wisdom.

Any views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this report, do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Images from left to right: InterPlay augmented reality app, a collaboration between Adana Tillman, the Akron Art Museum, and Bluecadet; Shelbi Toone, Peace on the Hilltop, mural, 2021, Columbus, OH; Shelbi Toone, Because of Them, We Can, mixed media on canvas, 2018, Columbus, OH

Images shown: InterPlay app, a collaboration between Adana Tillman, the Akron Art Museum, and Bluecadet; Shelbi Toone, Peace on the Hilltop, 2021, Columbus, OH; Shelbi Toone, Because of Them, We Can, 2018, Columbus, OH

What Museums Learned Leading through Crisis

AAM Member-Only Content

AAM Members get exclusive access to premium digital content including:

- Featured articles from Museum magazine

- Access to more than 1,500 resource listings from the Resource Center

- Tools, reports, and templates for equipping your work in museums

We're Sorry

Your current membership level does not allow you to access this content.

Upgrade Your Membership